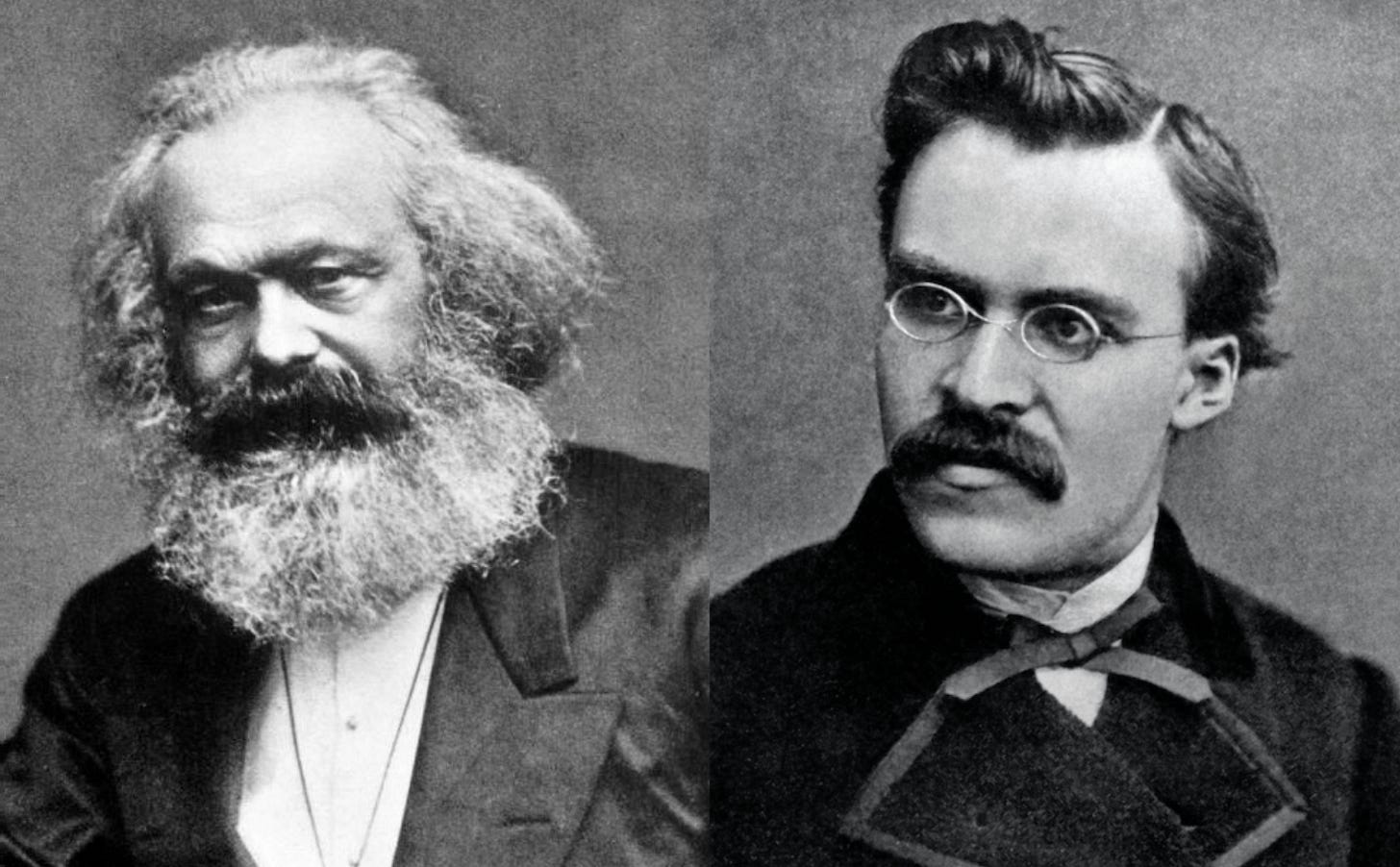

Nietzsche and Marx: The Roots of the Modern Right and Left

A Comparative Analysis (and Critique) of Friedrich Nietzsche and Karl Marx’s Revolutionary Views on History, Morality, Class Conflict, and the Broader 19th Century Landscape

Introduction

At first glance, aspects of Nietzsche’s argument seem quite compatible with Marxist theory, particularly the idea that conflict between opposing groups drives historical change. For example, Nietzsche, when describing his view of human history, wrote that “the two opposed forces, good and bad… have fought a terrible millennia-long battle” (30). Similarly, when Marx gave his view of history, he explained that “society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other — Bourgeoisie and Proletariat.” Both thinkers followed the 19th-century intellectual trend of describing humanity as two broad groups in constant conflict.

However, their arguments diverged in key ways that this essay will illustrate: First, Marx viewed history as the struggle between socioeconomic classes, while Nietzsche saw it as a conflict over morality and values, and as an assault on nobility. Second, while Marx viewed a proletariat revolution as an act of justice and progress, Nietzsche would question whether a revolution of this sort would actually be good for society. Finally, Nietzsche’s focus on moral values and on the superiority of aristocracy affected his judgment of the Revolution he did know –– the French Revolution.

Understanding Nietzsche and Marx’s Respective Views on History

Both Nietzsche and Marx responded to the creation, following the Industrial Revolution and the growth of liberal democracy, of a dominant bourgeois class, and both analyzed the way in which society had changed in the process. The consensus among the 19th-century liberals in Western and Central Europe was that these changes represented progress in humanity: both democratization and capitalism created human flourishing, and society was moving closer to egalitarianism. However, both Nietzsche and Marx dissented from this view, believing that their environment was fundamentally flawed and that society had deteriorated. The two men attributed this deterioration to different causes, though: Marx, to the oppression of the proletariat by the opposing force of the bourgeoisie, and Nietzsche, to the decline of aristocratic values and the rise of an opposing “slave morality.”

Nietzsche pointed to what he felt was the greatest example of a slave revolt, the revolt of the Jews, explaining that “the Jews… were able to obtain satisfaction from their enemies and conquerors through a radical revolution of their values… through an act of spiritual revenge” (16). Nietzsche explained that the Jews opposed the aristocratic “value equation” in favor of its opposite: the elevation of the lowly. This was strikingly different from Marx, who called for a revolt of an oppressed class fueled by the desire for socioeconomic justice, not moral justice. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx wrote that “the history of all… existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another.” Both thinkers emphasized the binaries that drive history, describing humanity in a reductive fashion. However, Nietzsche focused on opposed value systems, while Marx explicitly referenced class struggle. Another way to describe the contrast between the two thinkers is that Nietzsche and Marx had a very similar theory of history, with very different politics behind it. This raises the question: which thinker is right? Is it socioeconomics or morality that drives societal change?

Answering the Question: What Really Does Drive Social Upheaval?

The French Revolution is an interesting case study of Marx and Nietzsche’s diverging views. Nietzsche described the French Revolution as a revolt of morality in which Judeo-Christian values replaced the ruling aristocratic values in France. He metaphorically claimed that “Judea” has “once again achieved victory over the classical ideal with the French Revolution” (32). His decision to describe the French lower classes as Judea, which represents his concept of “slave morality,” shows that Nietzsche viewed the French Revolution as a moral revolution. But one of Nietzsche’s shortcomings may have been to misunderstand certain economic motivations as moral ones. Marx described the French Revolution quite differently in the Communist Manifesto: “The French Revolution… abolished feudal property in favour of bourgeois property.” For Marx, the French Revolution was really a revolt about socioeconomic class divisions, and a change in morality was simply its byproduct. And Marx had a point. According to HISTORY.com, the French Revolution was primarily driven by

“several years of poor harvests, drought, cattle disease, and skyrocketing bread prices that had kindled unrest among peasants and the urban poor. Many expressed their desperation and resentment toward a regime that imposed heavy taxes—yet failed to provide any relief—by rioting, looting and striking.”

Even if moral changes did follow the French Revolution, the primary motivation for the revolt of the French lower classes was socioeconomic disparity.

Explaining Nietzsche’s Fallibility

Why does Nietzsche focus only on moral change? And relatedly, why does he not mention the economic basis of these moral changes? For example, Marx would likely say that the nobility were only advancing their ideas about bravery and honor in order to reinforce their own power, ultimately rooted in their control of land. Interestingly, Nietzsche does not mention land or labor at all. One reason for this might be that Nietzsche respected the aristocracy and did not believe that there was anything immoral about the landowning class (or about the act of landowning itself). On the contrary, he felt that such ownership should be revered: “human history would be much too stupid an affair without the spirit of the nobility,” he wrote (16). For Nietzsche, the nobility, which to him embodied strength and dominance, represented a more natural way of life. Thus, he would not critique their social status and would instead celebrate it.

Nietzsche’s obsession with the nobility may have prevented him from clear historical analysis. While Marx viewed an event such as the French Revolution as societal justice, Nietzsche questioned whether the revolution was actual progress, calling it the end of “political nobleness” in Europe (32). Nietzsche was inherently anti-egalitarian and consistently rejected the notion that societal progress towards a more egalitarian ideal actually made life better. He believed that the modern system of morality, which derives from the Judeo-Christian revolution, encourages weakness: “the poor, the powerless, the lowly… are good. The suffering, deprived, sick, ugly are also the only pious” (16). Nietzsche believed that this reversed hierarchy was backwards and “doom-laden.”

In one respect, Nietzsche’s critique of the French Revolution was undoubtedly correct. The French Revolution was an extremely destructive event that led to the death of thousands of innocent people. But the Revolution did usher in social changes and human progress, and it is these elements that Nietzsche does not discuss. This is odd for a thinker who spent so much time rooting his beliefs in historical phenomena. But Nietzsche may have been blinded by his own oppositional thinking: love of aristocratic values, and contempt for the weakness and ressentiment of the commoner.

Nietzsche’s focus––to the point of tunnel vision––on the morality of superiority, love of the aristocracy, and anti-egalitarian sensibilities clouded his vision of history, as he failed to recognize significant societal progress. He criticized modern society for suppressing the natural instincts of man, believing that our newfound morality had not actually produced a net benefit. However, societal advancements, such as the acceptance of capitalism and democracy, have drastically improved our quality of life, increased our life spans, reduced world poverty -- and brought us closer to human flourishing.

Applying This Comparison to Modern Political Ideologies

Similar to Nietzsche and Marx, both the contemporary far left and right have a reductive view of the world. At the root of this problem is a lack of cross-cultural understanding, which leads to broad and often inaccurate generalizations from both sides. We’ve seen this culminate in political violence, social unrest, and flat-out rioting: the insurrection on January 6th and the assassination of Charlie Kirk act as two contemporary examples. Broadly, and albeit reductively speaking, today’s extreme left often glorifies oppressed groups and peoples, and advocates for societal reconstruction to advance humanity closer to what it believes is a more egalitarian world. In contrast, on the global right, we see a very visceral rejection of progressive values, the sense that our culture has lost “toughness,” and the subsequent desire to go back to and recreate a simpler, more “natural” state of humanity. There are striking parallels to Nietzsche and Marx here: Nietzsche too believes that modern morality has suppressed man’s most fundamental instincts, referring to that morality as a “regression, a poison, a temptation, and a narcotic.” “I am an opponent of the modern softening of feelings,” he says (5). Similarly, the aforementioned leftist paradigm echoes Marx’s desire for a proletariat revolution. In fact, much of modern leftist thought is derived from Marx. However, when discussing the extreme right and left, we must discuss the Horseshoe Theory: the idea that both political extremes eventually end up being more similar to each other than they are to the rest of the political spectrum. For example, both the left and right question the validity of the social contract, and view it as obsolete. Similarly, both Nietzsche and Marx share these concerns. For example, Nietzsche says that “the state” is really just “a race of conquerors and lords which organized in a warlike manner” and “made its appearance as a terrible tyranny… a crushing and ruthless machinery.” He asserts that “the contract” (a reference to the social contract) has been abandoned (58). Likewise, Marx believed that political structures, which in theory should protect the natural rights (like property) of the people, in reality just protect the property and power of the bourgeoisie -- also suggesting the failure of the social contract. The subtle similarities between these two 19th-century thinkers perhaps suggest something deep about our human political psyche as a whole. Perhaps our modern political zeitgeist is not such an aberration.

Works Cited:

HISTORY.com Editors. “French Revolution: Timeline, Causes & Dates | HISTORY.” HISTORY, 9 Nov. 2009, www.history.com/articles/french-revolution.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. “Manifesto of the Communist Party.” Marxists.org, Feb. 1848, www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/.